Be the first to measure and contribute air quality data to your community

55.6K people follow this city

AIR QUALITY DATA SOURCE

Find out more about contributors and data sources| Weather | Few clouds |

| Temperature | 77°F |

| Humidity | 100% |

| Wind | 2.3 mp/h |

| Pressure | 29.8 Hg |

| # | city | US AQI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bandung, West Java | 114 |

| 2 | Jakarta, Jakarta | 95 |

| 3 | South Tangerang, Banten | 88 |

| 4 | Surabaya, East Java | 84 |

| 5 | Semarang, Central Java | 59 |

| 6 | Bogor, West Java | 57 |

| 7 | Pekanbaru, Riau | 57 |

| 8 | Palembang, South Sumatra | 23 |

| 9 | Palangkaraya, Central Kalimantan | 21 |

(local time)

SEE WORLD AQI RANKING

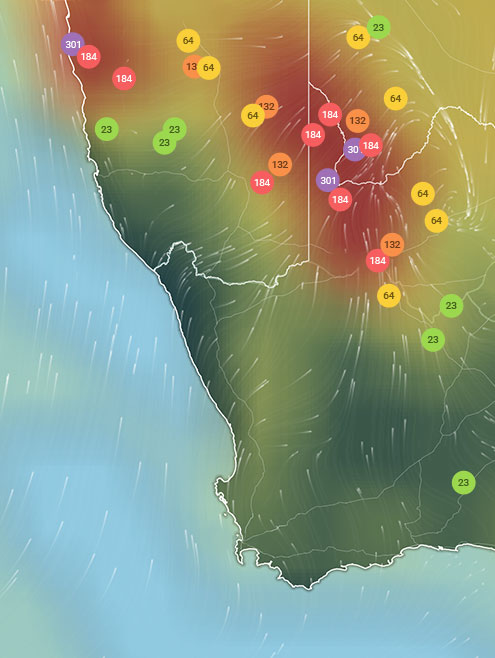

US AQI

62*

live AQI index

Moderate

| Air pollution level | Air quality index | Main pollutant |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate | 62* US AQI | PM2.5 |

| Pollutants | Concentration | |

|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | 17.2*µg/m³ | |

| PM10 | 20.9*µg/m³ | |

| O3 | 16.6*µg/m³ | |

| SO2 | 35.5*µg/m³ | |

PM2.5

x3.4

PM2.5 concentration in Makassar is currently 3.4 times the WHO annual air quality guideline value

| Sensitive groups should reduce outdoor exercise | |

| Close your windows to avoid dirty outdoor air GET A MONITOR | |

| Sensitive groups should wear a mask outdoors GET A MASK | |

| Sensitive groups should run an air purifier GET AN AIR PURIFIER |

| Day | Pollution level | Weather | Temperature | Wind |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Today | Moderate 62 AQI US | 86° 77° | ||

| Saturday, Apr 27 | Good 37 AQI US | 86° 77° | ||

| Sunday, Apr 28 | Good 33 AQI US | 86° 77° | ||

| Monday, Apr 29 | Good 27 AQI US | 87.8° 77° | ||

| Tuesday, Apr 30 | Good 16 AQI US | 78.8° 77° | ||

| Wednesday, May 1 | Good 17 AQI US | 86° 77° | ||

| Thursday, May 2 | Good 19 AQI US | 84.2° 75.2° |

Interested in hourly forecast? Get the app

Makassar is situated on the island of Sulawesi on the southwest coast. It is the largest city in the region and occupies a strategic position on the shipping routes which travel through the Makassar Strait. The air quality index (AQI) registered a level of 29 US AQI in December 2020, which places it in the “Good” category as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The main recorded pollutant was PM2.5 with a concentration of 7.1 µg/m³.

It also is conveniently located between the northern and southern provinces of south Sulawesi. Rapid growth is unavoidable under these circumstances. As a result of this, Makassar city is a mix of residential, commercial and industrial areas. And is subject to the pollution this causes. Because of this variation of uses, it is important to monitor air pollution very carefully.

Makassar is not a particularly extensive industrial city, although it does have some small industries based here, accounting for just over 20 per cent of the city’s economy. Its main source of income is from shipping and the service industry.

Makassar has an efficient public transportation system called “pete-pete”. These are basically minibuses that have been modified to carry more passengers. Another form of transportation is the becak. This is basically a motorbike that has been modified by the addition of a passenger section attached to the framework. In 2014 the government introduced a bus rapid transit or BRT system which operates smaller vehicles capable of carrying 40 passengers. 20 can be seated whilst the other 20 need to stand.

Perhaps one of the main sources of air pollution in Makassar is from the surrounding agricultural areas. In developing countries such as Indonesia, the practice of “slash and burn” is carried out on a regular basis. This is a crude technique but unfortunately very efficient. Mostly carried out by small farmers but encouraged by large often international companies who are demanding more and more land in order to keep up with demand. Massive plantations of just one product are taking over any available land. This demand is for palm oil of which Indonesia is the largest producer. A huge amount of 31 million metric tonnes of palm oil were produced in 2015 which was an increase of 50 per cent since 208. The current level of production is unknown but could easily be twice that amount as palm oil is being used in the production of more and more goods, each year.

The average annual levels of sulphur dioxide (SO2) were recorded as 76 μg/m3, carbon monoxide (CO) - 1041 μg/m3, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) - 43.2 μg/m3 , ozone (O3) - 54.5 μg/m3, lead (Pb) - 0.7 μg/m3, TSP -188 μg/m3 and PM10 were 54.6 μg/m3. These figures are then compared to standards suggested by the Indonesia National Ambient Air Quality Standard (INAAQS) and to the guidelines laid down by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

During the autumn, much of south-east Asia has been enveloped by smoke and fog which originated from the annual slash and burning in Indonesia. The dry season lasted an unusually long time this year which dried many areas to a tinder. Once the fires were started, they were virtually impossible to extinguish and continued burning for almost 10 weeks. When a tropical storm blew up, all of these noxious pollutants were carried in the air and covered most of the country, together with neighbouring Singapore and Malaysia. Schools, airports and other public services had no choice but to cease operations until the situation improved.

The place to start is the slash and burn practice, which the Indonesian government call a “crime against humanity”. Around 75 per cent of Indonesia’s 472 million acres of land is classed as State Forest Land. Even though a percentage of this land has in fact no tress. Instead, it is covered by small saplings and bushes. This makes it ideal for slash and burn.

Very often, small families and groups of farmers live on these lands but have no legal rights to be there. Many of them, therefore commit illegal acts without realising what they have done. They sometimes farm small plots of their own, but most often, they work informally for the large plantation managers. Because they have no land of their own or indeed have any legal rights to purchase land for themselves, there is very little incentive for them to act responsibly. Many families have been practising these procedures for years and therefore know no different.

Many are unaware of central government practices but even if they were told about their rights, the majority of people do not have the knowledge or the resources to change the situation.

In order to move forward, many families need to be taught the basics of business. Through an established local partnership, 16,000 farmers have already obtained legal rights to farm State Forest Land. Together they bow have access to almost 40,000 acres of land, Slash and burn is strictly prohibited. Their income now is derived from coffee, rice, fruit and nuts.

The health effects of pollutants have been studied using various experimental models (exposure to pollutants from cells, tissues, animals and volunteers) and epidemiological (pollution episodes, comparison of exposed versus unexposed populations, healthy versus diseased etc.). When looked at individually, each of these types of studies has strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, it is the set of results obtained by applying these different techniques in the study of pollutants, which gives the greatest value to the effects found. Adverse effects depend, on the one hand, on the concentration and duration of exposure and, on the other, on the susceptibility of the exposed persons and the initial state of their health.

A strong healthy individual will be more able to deal with slightly polluted air when compared to someone who is already suffering from respiratory problems.

No locations are available.