Get a monitor and contributor to air quality data in your city.

231K people follow this city

AIR QUALITY DATA CONTRIBUTORS

Find out more about contributors and data sources| Index | Low | ||

| Tree pollen | Low | ||

| Grass pollen | None | ||

| Weed pollen | None |

| Weather | Scattered clouds |

| Temperature | 53.6°F |

| Humidity | 50% |

| Wind | 5.7 mp/h |

| Pressure | 29.6 Hg |

| # | city | US AQI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reading, England | 53 |

| 2 | Hayes, England | 52 |

| 3 | Cardiff, Wales | 41 |

| 4 | Southampton, England | 41 |

| 5 | West End of London, England | 41 |

| 6 | Motherwell, Scotland | 39 |

| 7 | Leicester, England | 38 |

| 8 | Edinburgh, Scotland | 37 |

| 9 | London, England | 37 |

| 10 | Luton, England | 37 |

(local time)

SEE WORLD AQI RANKING

| # | station | US AQI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Waltham Crooked Billet | 65 |

| 2 | Euston Road | 54 |

| 3 | Earls Court Road | 53 |

| 4 | Waltham Forest Dawlish Rd | 53 |

| 5 | Allergy Cosmos in Battersea | 50 |

| 6 | Camden Kerbside | 50 |

| 7 | Hammersmith Town Centre | 50 |

| 8 | Kingscourt Road | 50 |

| 9 | Hounslow Brentford | 45 |

| 10 | Westhorne Avenue (reference co-location) | 45 |

(local time)

SEE WORLD AQI RANKINGUS AQI

37

live AQI index

Good

| Air pollution level | Air quality index | Main pollutant |

|---|---|---|

| Good | 37 US AQI | PM2.5 |

| Pollutants | Concentration | |

|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | 9µg/m³ | |

| PM10 | 14.1µg/m³ | |

| O3 | 69.5µg/m³ | |

| NO2 | 24.9µg/m³ | |

| SO2 | 4.2µg/m³ | |

| CO | 100µg/m³ | |

PM2.5

x1.8

PM2.5 concentration in London is currently 1.8 times the WHO annual air quality guideline value

| Enjoy outdoor activities | |

| Open your windows to bring clean, fresh air indoors GET A MONITOR |

| Day | Pollution level | Weather | Temperature | Wind |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuesday, Apr 23 | Good 29 AQI US | 50° 41° | ||

| Wednesday, Apr 24 | Good 31 AQI US | 46.4° 39.2° | ||

| Thursday, Apr 25 | Good 40 AQI US | 53.6° 37.4° | ||

| Today | Good 37 AQI US | 53.6° 35.6° | ||

| Saturday, Apr 27 | Good 33 AQI US | 53.6° 42.8° | ||

| Sunday, Apr 28 | Good 23 AQI US | 48.2° 41° | ||

| Monday, Apr 29 | Good 24 AQI US | 57.2° 39.2° | ||

| Tuesday, Apr 30 | Good 36 AQI US | 62.6° 44.6° | ||

| Wednesday, May 1 | Moderate 56 AQI US | 62.6° 50° | ||

| Thursday, May 2 | Moderate 57 AQI US | 60.8° 51.8° |

Interested in hourly forecast? Get the app

Air pollution in London has been a long-term health concern for the United Kingdom’s capital. The city is regularly found to have some of the highest air pollution levels in the country, and coupled with housing 9 million of the UK’s population of 67 million, this results in high levels of exposure presenting a health risk to numerous residents. London air pollution levels are frequently found to break both UK legal and World Health Organization (WHO) limits for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and WHO limits for PM2.5. While the city has come a long way since the infamous, ‘pea-soup’ Great Smog of 1952, and air pollution has become less visible in the capital, it still presents severe health and economic risks to the city.

The main pollutants of concern in London are fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which are generated in London from urban transport and heating of homes, among other sources. NO2, created from the combustion of fossil fuels, can lead to lung irritation and increases the risk of respiratory diseases, while long-term exposure has also been linked to increased risk of premature death. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 can contribute to respiratory infections, aggravating asthma, cardiovascular disease, and lung cancer.

An influential study conducted by King’s College London in 2015 estimated that London PM2.5 pollution contributes towards 3,500 premature deaths in London annually, while NO2 contributes towards 5,900 premature deaths, making a total health burden of 9,400 premature deaths per year.1 This represents a substantial proportion of the UK’s estimated national health burden of 40,000 premature deaths annually, estimated by the Royal College of Physicians in 2016.2 The economic cost of this loss of London life is estimated to be up to £3.7 billion ($4.8 billion).1

A challenging aspect of London’s air quality problem is that, given the geographical and economic diversity of the city, air pollution affects some parts of the population disproportionately. Given transport’s significant contribution towards NO2 and PM2.5 levels, there is growing evidence of the increased health risks posed to parts of the population who are more exposed to busy roads. For example, King’s College London found that living near a busy road in London may contribute to 230 hospital admissions for strokes every year, while also stunting lung growth in children by 12.5%.3 Proximity to busy roads also often correlates to living in deprived areas in London, thus also disproportionately affecting low-income communities.4 Numerous studies have also drawn links between poor London air quality disproportionately affecting black and ethnic minority people within the city, although the causal reasons for this correlation remains unclear.5,6

Children and the elderly are another group which are particularly vulnerable to the health impacts of air pollution in London. In particular, school children have been shown to face disproportionate risk from air quality at schools in London due to various factors. 25% of school children have been shown to attend schools located in areas where NO2 levels are above the healthy and legal limit.7 Additionally, another study suggests that children are exposed to five times higher levels of air pollution during the walk to school, than is normal during other times of the day.8

For at least the past 3 years, London’s annual average PM2.5 level has exceeded the WHO’s target limit of 10µg/m3, with a 2019 average PM2.5 level of 11.4µg/m3. While this correlates to a London AQI indicator of “1, Low” on the UK’s Daily London Air Quality Index, this is still is 14% above the WHO recommendation. In broader context, London’s 2019 PM2.5 level ranked as the 17th most polluted capital city out of 29 capitals in Europe, with Sarajevo (34.1 µg/m3), Paris (14.7 µg/m3) and Vienna (12.3 µg/m3) all ranking higher, in IQAir’s World Air Quality Report 2019.9 Cleaner European capitals than London in 2019 include Amsterdam (10.7 µg/m3), Madrid (9.2 µg/m3) and Tallinn (5.5 µg/m3).

Most London air pollution comes from road transport, as well as domestic and commercial heating systems. While road transport is estimated to contribute significantly to the UK’s urban levels of NO2 (42%), road transport is estimated to only contribute 12% towards local levels of PM2.5. Conversely, the largest contributor of PM2.5 in cities is estimated to come from wood and coal heating.10 As a consequence of transport’s significant contribution to NO2 pollution in London, concentrations are generally found to be higher at roadside locations than city background levels. London NO2 data shows that over a 1-year period between August 2018 to July 2019, background NO2 levels averaged 28.4 µg/m3, while roadside NO2 levels averaged 44.9 µg/m3 (exceeding the UK’s legal annual mean NO2 limit of 40 µg/m3).11

Ambient air pollution does not respect boundaries, and while London air pollution is made up of some localized emissions from transport, heating and industry, it also received a large amount of transboundary pollution from outside the city. Research estimates that 75% of London’s particulate matter pollution comes from outside the city, while 18% of London’s ambient NO2 emissions come from outside the city.7

Air pollution in London can also be influenced by seasonal weather factors. For example, colder conditions during winter months and low winds can lead to emissions being trapped near the ground in what is also known as a cold temperature inversion, prolonging and intensifying spells of air pollution. These winter smogs in the UK are also colourfully referred to as ‘pea-soupers’. London’s infamous Great Smog of 1952 took place during four days of the winter month of December (5-9th), and this severe smog episode was caused by emissions from excess coal burning to heat homes, combined with unusually cold temperatures and windless conditions which trapped the smog. It eventually dispersed when the weather changed. More recently, London experienced an intense 4-day smog episode between 12-15 December 1991, where NO2 levels broke records as the highest recorded to date, since monitoring began in 1970.12 Conversely, London’s warmer summer months can lead to summer smog episodes. These are typically caused by nitrogen dioxide reacting with hydrocarbons in sunlight, to form ozone. Greater London experienced a notable summer smog episode in 1995 following continuously high temperatures exceeding 30°C being recorded.13

While London still struggles against air pollution in the city, air pollution management has evolved significantly since the dramatic events of the Great Smog of 1952. Following this event, the UK has made efforts to reduce its reliance on coal as part of the national energy mix, and the Clean Air Act was introduced in 1956 to start closer regulation and management of UK air quality.

According to IQAir’s 2019 World Air Quality Report, London’s aggregated annual average PM2.5 level has decreased slightly over the past 3 years, while still remaining above the WHO’s recommended limit of 10 µg/m3. Its 2017 average level was 12.7 µg/m3; 2018 averaged 12.0 µg/m3; while 2019 averaged 11.4 µg/m3. NO2 levels are also shown to have improved slightly over time, with a 9% decrease recorded between 2013-2016.14 However, NO2 levels are not falling as quickly as predicted, nor falling significantly from hazardous levels at key areas such as schools. 15

London is driving several initiatives to tackle citywide air pollution, under London Mayor Sadiq Khan who took office in 2016. After having implemented a Low Emission Zone (LEZ) in February 2008, on 8 April 2019, London took the further step of introducing the world’s first Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ). The ULEZ covers a defined area within central London, and requires vehicles to meet stringent emissions standards, or else pay a fine to enter the zone. These penalties are active throughout the week. Since its inception, early data shows a significant improvement to NO2 levels within the ULEZ, with estimated reductions of 35% of NOx emissions from transport.16 London is cited as a leader in expertise on ULEZ by air quality experts.17

In addition to the ULEZ, other initiatives tackling pollution from transport are also underway in the capital. This includes ensuring that all new double-decker buses are hybrid, hydrogen, or electric-powered from 2018, and introducing a dozen new low emission bus zones for some of London’s most polluted areas by 2019.

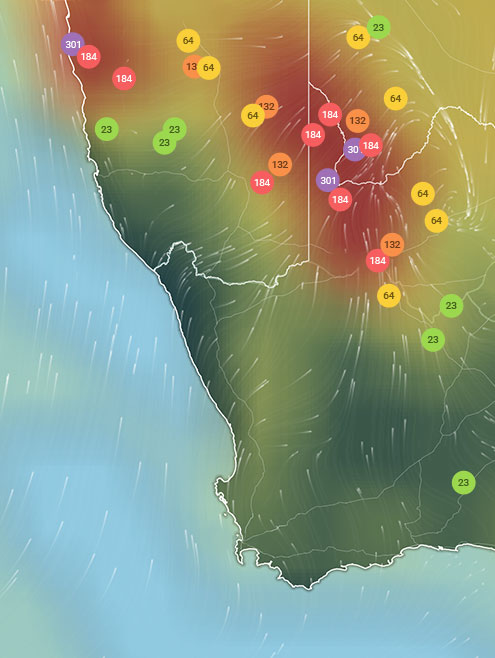

As a general rule, areas with higher recorded levels of pollution tend to be situated more centrally within London, with cleaner air quality found towards the outer suburbs.

According to one study comparing annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 across London’s 32 boroughs, weighted by population, all boroughs exceed the World Health Organisation’s recommended limit of 10 µg/m3 by more than 20%. The two boroughs with the highest PM2.5 concentrations by population lie in the heart of the city, the City of London (15.7 µg/m3) and Westminster (15.0 µg/m3), followed by inner London boroughs Camden (14.5 µg/m3), Kensington and Chelsea (14.5 µg/m3) and Islington (14.2 µg/m3). In contrast, the three boroughs with lowest levels of PM2.5 – although these do still exceed the WHO guidelines – are all situated in outer London: Havering (12.1 µg/m3), Bromley (12.4 µg/m3) and Hillingdon (12.5 µg/m3).18

According to recent NO2 levels, 4 out of the 10 places with highest recorded NO2 across the UK were in London in 2020. Within the top 10 spots for NO2 levels in London, these are predominantly located within central or inner London, reflecting higher levels of traffic density. The most polluted places in London for NO2, based on an annual average measurement, are the Strand (City of Westminster, 88 µg/m3), Walbrook Wharf (City of London, 87 µg/m3), Marylebone Road (City of Westminster, 85 µg/m3), Euston Road (Camden, 82.3 µg/m3), and Cromwell Road/Earl’s Court Road (Kensington/Chelsea, 77.4 µg/m3).19 The top 4 of these locations breach the UK’s legal annual limit of 40 µg/m3 NO2 by more than double.

Real-time air quality levels can be viewed on IQAir’s London air quality map at the top of this page, together with a London air quality forecast for each area.

Numerous major roads in London have gained notoriety for being the city’s most polluted at different times, mostly due to breaching annual NO2 limits within a matter of days during the early days of the year. As part of the UK’s NO2 air quality regulation, no location should record an NO2 measurement above 200 µg/m3 more than 18 times within a year. However, this limit has been broken shockingly fast on numerous occasions. In 2015, Oxford Street broke this limit within just 4 days of the new year; in 2016, Putney High Street broke this limit by 8 January, and subsequently an alarming 1,200 times throughout the year. In 2017, Brixton Road in Lambeth broke the annual limit just 5 days into the year, while in 2018 Brixton Road was again the first location to break the annual NO2 limit, with a slightly improved timeline of 30 days into the year. 20 This is, however, clearly still extremely insufficient progress towards achieving the annual limit the regulation is intended to impose.

According to IQAir’s World Air Quality Reports, Paris air quality has reported consistently higher levels of citywide PM2.5 pollution over the past few years than London. While London’s PM2.5 levels appear to decrease slightly over the past 3 years (12.7 µg/m3 in 2017; 12.0 µg/m3 in 2018; 11.4 µg/m3 in 2019), a similar pattern is not so evident in Paris (15.4 µg/m3 in 2017; 15.6 µg/m3 in 2018; 14.7 µg/m3 in 2019).9 Both cities struggle to manage the same key pollutants, of NO2 and particulate matter. While research suggests that NO2 levels are decreasing in both cities, based on current progress, researchers estimate that Paris’ current rate of decrease may allow them to achieve the European annual target of 40 µg/m3 within 20 years, while London is on track for a significantly longer time of 193 years.21

In terms of hazardous PM2.5, New York air quality has reported consistently lower levels of fine particle pollution than London over the past few years. While between 2017-2019, London’s annual average PM2.5 concentration ranged from 12.7 µg/m3 to 11.4 µg/m3, New York has reported fairly steady, lower annual averages of 6.8 µg/m3 (2017), and 7 µg/m3 (2018, 2019). These values are within the WHO’s recommended limit of 10 µg/m3, although the WHO emphasizes that there is no known "safe" threshold for PM2.5 under which no negative health impacts are observed. One key factor credited with achieving this notable different in pollution levels between New York and London, is the European policy which encouraged the uptake of diesel vehicles for climate reasons around the millennium.22 The effects of this policy in contrast with United States air quality management is made starkly clear by the difference in the number of vehicles in each country: in the US, diesel vehicles have a market share of only 3%, compared to a 50% share within the UK.23 The UK government’s pledge to phase out diesel vehicles by 2040 may help to address this imbalance, although critics suggest this timeline is not ambitious enough.24

+ Article resources

[1] Heather Walton, David Dajnak, Sean Beevers, Martin Williams, Paul Watkiss and Alistair Hunt. "Understanding the Health Impacts of Air Pollution in London", Mayor of London and London Assembly website, 14 July 2015.

[2] Royal College of Physicians. "Every breath we take: the lifelong impact of air pollution", Royal College of Physicians website, February 2016.

[3] KCL: Williams M et al (2019). "Personalising the Health Impacts of Air Pollution – Summary for Decision Makers", Imperial College Environmental Research Group website, 25 November 2019.

[4] Mayor of London and London Assembly. "Health and exposure to pollution", Mayor of London and London Assembly website, n.d.

[5] Adam Vaughan. "London’s black communities disproportionately exposed to air pollution – study", The Guardian, 10 October 2016.

[6] Sam Wong. "Ethnic minorities and deprived communities hardest hit by air pollution", Imperial College website, 26 January 2015.

[7] Richard Howard. "Up In The Air - How to Solve London’s Air Quality Crisis: Part 1", Policy Exchange website, 2016.

[8] King’s College London. "Children exposed to five times more air pollution on school run", King’s College London website, 22 October 2019.

[9] IQAir. "Most polluted cities", IQAir website, n.d.

[10] Kathrin Enenkel, Valentine Quinio and Paul Swinney. "Cities Outlook 2020", Centre for Cities website, 27 January 2020.

[11] "London Datastore", Mayor of London & London Assembly. Mayor of London website, n.d.

[12] J.S. Bower, G.F.J. Broughton, J.R. Stedman, M.L. Williams. "A winter NO2 smog episode in the U.K.", Atmospheric Environment (28)3, February 1994.

DOI: 10.1016/1352-2310(94)90124-4

[13] DEFRA. "Summer Smog Episodes", DEFRA website, n.d.

[14] Damian Carrington. "Air pollution falling in London but millions still exposed", The Guardian, 1 April 2019.

[15] London Air. "What is Nitrogen Dioxide?", Imperial College Environmental Research Group ‘London Air’ website, n.d.

[16] Mayor of London. "Central London Ultra Low Emission Zone – Ten Month Report", Mayor of London website, April 2020.

[17] Jonathan Watts. "Blue-sky thinking: how cities can keep air clean after coronavirus", The Guardian, June 7, 2020.

[18] GLA & TFL Air Quality. "London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (LAEI) 2016", Mayor of London & London Assembly website, 2016.

[19] Friends of the Earth. "Mapped: More than one thousand locations in England still breaching air pollution limits". Friends of the Earth website, July 29, 2020.

[20] Damian Carrington. "London breaches annual air pollution limit for 2017 in just five days", The Guardian, 6 January 2017.

[21] Anna Font, Lionel Guiseppin, Véronique Ghersi, Gary W. Fuller. "A tale of two cities: is air pollution improving in Paris and London?", Environmental Pollution (249), June 2019.

DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.040

[22] Martin Rosenbaum. "Why officials in Labour government pushed ‘dash for diesel’", BBC News, November 16, 2017.

[23] Emma Howard. "Toxic air: why is New York cleaner than London?", Unearthed, 19 September 2016.

[24] Greenpeace. "Air pollution", Greenpeace website, n.d.

14Contributors

2 Government Contributors

1 station

Non-profit organization Contributor

14 stations

Educational Contributor

2 Corporate Contributors

1 station

30 stations

3 Individual Contributors

1 station

1 station

1 station

5 Anonymous Contributors

5 stations

7 Data sources